Making Movement Changes in the Weight Room

You can’t outcue a movement deficiency. These are words we live by at Driveline Baseball and that’s what our makes our assessment process so vital for getting our athletes results. Individually, our assessments don’t provide nearly as much value as they do as a whole. However, once we combine the biomechanics report and throwing videos with the range-of-motion assessment and VBT testing, that’s where the real magic can happen.

When Mariners reliever Dan Altavilla came to Driveline, his situation was unlike many of those that come here. Most athletes come to Driveline to increase velocity, improve strength, or develop a pitch using Rapsodo and edgertronic video. While Dan did work on pitch design remotely, today we’re going to focus on how the rest of Dan’s assessment focused his programming. Considering Dan’s solid big-league numbers, a peak velocity of 100.46 mph last year, and his exceptional baseline strength, finding the biggest limiting factor was a bigger challenge for us.

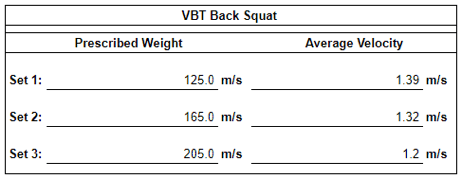

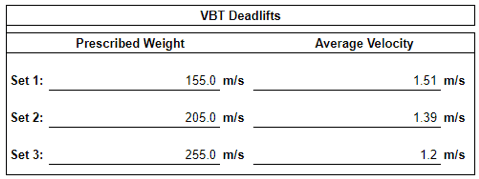

After missing some time with an injury in 2018, Dan knew that he needed to work on improving mobility to his muscle-bound frame. Which raises the question, How will adding mobility decrease the chance of injury? From looking at his VBT testing, it’s easy to see that he can put a lot of force into the ground, but what happens when that force moving up the kinetic chain can’t be absorbed? This video from our Director of Performance, Sam Briend, shows how that energy is transferred from the lower half to the arm.

Assessment Findings

The first thing we identified through Dan’s range-of-motion assessment was a lack of external rotation in his hips. Lacking hip external rotation can limit a pitcher’s ability to hold torque in the rear hip as the center of mass moves down the mound. Think about the squat and deadlift cue: “screwing the feet into the floor.” The point of screwing the feet is to stabilize the hips from being pulled towards the midline. When an athlete can hold torque in his rear hip, it allows the pelvis rotation to be driven by the glute rather than femoral internal rotation. In Dan’s baseline throwing videos, you can see his inability to hold tension in his rear hip as his center of mass moves towards the Plyo Ball ® wall. This can lead to a late pelvis rotation after foot contact, which puts him in a bad spot to have an effective lead-leg block.

The lead-leg block is a by-product of everything that happens before foot contact. You can see the effect that pelvis rotation has on the lead leg from this sugar packet and a butter knife from our biomechanist Anthony Brady:

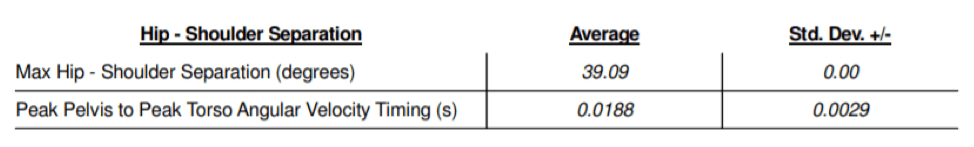

Another issue we found in Dan’s range-of-motion assessment was a lack of thoracic rotation. Having thoracic rotation aids in creating hip and shoulder separation. As the pelvis opens, the torso has to counter rotate in order to create separation. If an athlete lacks thoracic rotation to his counter-rotation direction, his torso will rotate at the same time as his pelvis. The thoracic rotation is what we’re able to measure in our mobility assessment; we wanted to see how that number compares to how Dan moves dynamically in his biomechanics report.

When assessing hip and shoulder separation, the timing between peak-pelvis and peak-torso angular velocities is arguably more important than the degree of separation. Dan’s biomechanics report shows that while his degree of hip-shoulder separation was sufficient at 39 degrees, the timing between peak-pelvis and peak-torso angular velocities was just 0.0188 seconds, which is on the lower end of what we see.

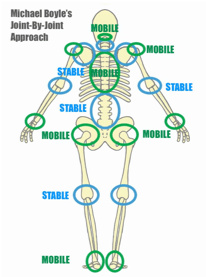

This is important, because if we look at the joint-by-joint approach, we know that the hips should be mobile, the lumbar spine stable, and the thoracic spine mobile. Therefore, if an athlete lacks range of motion or strength in his hips, the hips will stabilize to protect themselves, which causes a compensatory effect that forces the lumbar spine to be mobile and limits the range of motion through the thoracic spine.

Sometimes addressing a thoracic-mobility issue means addressing the hips and pelvis. Knowing that Dan lacked hip external rotation in both hips, we knew that if we worked on increasing range of motion in his hips and strengthening that new range of motion, the benefits could potentially work up the chain.

Programming

Once you’ve assessed an athlete, it’s important to take a step back and look at the big picture. As you’ll see, you can use the assessment to better target what you want to improve from when they first get to the gym to when they leave.

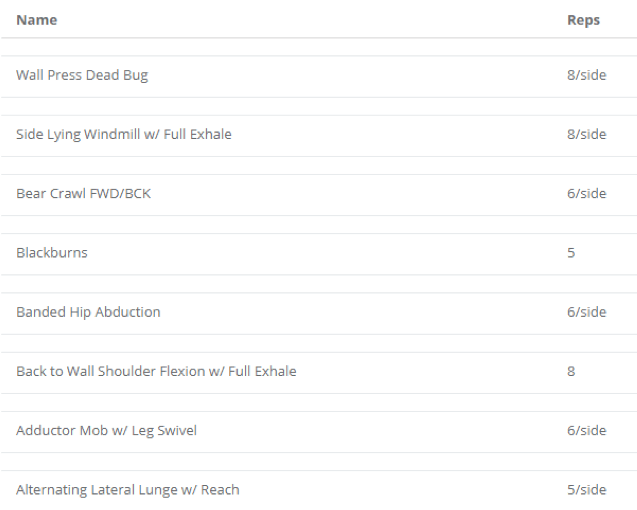

Warm Up

Based on the information from above, we designed a daily warm-up to attack these specific movement deficiencies. The objective of the warm-up is to get the athlete in better alignment prior to whatever activity he is going to do. It should progress from general exercises that address the athlete’s deficiencies to specific exercises that prime the body for what he is about to do.

Looking at his warm-up, we have Wall Press Dead Bug and Bear Crawl in there to address anterior core and pelvis stability that could be leading to his limited hip external rotation. Most anterior core exercises stabilize the hip external rotators. The Side Lying Windmill w/ Full Exhale is to address the lack of thoracic spine rotation.

Once we get through the “corrective exercises” we move into more movement-based exercises that prime him for the movement he’s about to do (pitching) and also address his deficiencies. That’s where the Banded Hip Abduction and Alternating Lateral Lunge w/ Reach come into play. The Banded Hip Abduction targets the gluteus medius, which is the prime mover for hip external rotation, and the Lateral Lunge is a frontal-plane exercise that helps him feel the load of the hip that he is lunging into.

Using Med Balls for Patterning

Since he had just finished a full season, we wanted to stay away from a high volume of rotational med-ball work; however, there is some value to patterning movement with med-ball exercises so early in the offseason, so we programmed more anti-rotation med-ball exercises that helped pattern the movement we were looking to improve when pitching. The Half Kneeling Med Ball Scoop Toss forced him to stabilize his lead leg as he rotates the medicine ball over it into the wall.

Once we were able to get into some more high-intensity rotation exercises, we used the Step Back Med Ball Shotput throw to help address his inability to hold torque in his rear hip, and the Split Stance Recoil Rollover Throw to Wall to add a rotational component to an exercise designed to use the lead leg to propel the trunk into flexion.

The Lifting Program

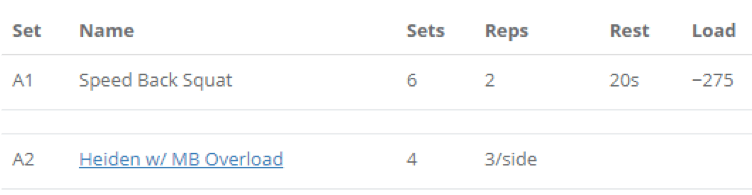

After a month of cleaning up some technique flaws, we got right into dynamic-effort work because spending too much time doing maximum-strength work would be disadvantageous for Dan based on where his strength levels were. In the one-month technique on-ramp, we lived in the four-rep range and kept the load the same each week, focusing on quality of movement.

Once we got into dynamic-effort work, he paired squats in the strength/speed velocity range (0.75-1.0 m/s or 50-60% of a one rep max) with overload jumps. Because he was so muscle bound, the extra load for the jumps allowed him to summon that extra tension for jumps before transitioning into a more true-speed phase.

As far as addressing movement deficiencies in the weight room, we used a variety of methods, including adding tempo to accessory exercises to increase stability in the hips and pairing those with mobility exercises. An example is a Barbell Romanian Deadlift with a two second isometric paired with a Pigeon Pose to Half Kneeling. The Pigeon Pose to Half Kneeling takes the traditional pigeon pose, which stretches the hip into external rotation, and adds a movement to force the athlete to move in and out of hip external rotation. The goal is to increase the range of motion with the mobility exercise and then strengthen within that new range of motion.

Overview

Clip of Dan throwing during this spring training

This a solid example of why an integrated approach is so crucial for getting athletes results. It greatly benefits athletes for their coaches in multiple domains to look over information and discuss what each athlete needs. A strength coach can’t decide to stay in his lane and just focus on getting athletes stronger, because there will eventually be an athlete like Dan who is already strong enough and needs to focus his attention on other things. A pitching coach can’t just cue an athlete to “stay in his back hip” or “rotate his pelvis” because the athlete might not have the range-of-motion capabilities to do so.

In order to work towards achieving the athlete’s goals and needs determined during the assessment process, you need an R&D department that can tell you what is happening and a High Performance department that can help fill in the gaps about why it is happening. Once those two things are solved, the High Performance department and pitching coaches can work together to develop a plan to directly attack the issues at hand.

This article was written by High Performance Trainer Kyle Rogers

Comment section