Command Training and a Closer Look at the Speed Accuracy Trade-Off

Throwing strikes is hard. Previously, we’ve discussed the mechanical and kinesiological factors that go into both throwing strikes and command issues. There are certainly psychological factors to consider as well.

We speak about the importance of intent when discussing velocity, but it also has a very similar significance for command. Intent is a requirement to command the baseball, just like it is to throw hard. You don’t produce elite command by just throwing as hard as possible. Ideally, we try to throw as hard as possible to a intended location or target. Moving forward in this post, we will be speaking about intent as being interchangeable with effort.

Command is a skill and should be trained as such. Continually yelling at a pitcher to “throw strikes,” or constantly forcing him to make conscious mechanical changes, is not an effective way to improve command. In many cases, the outcome of this will be the complete opposite. We know this.

We will discuss how we train command and how it can be implemented into team practice in an upcoming post. Before we get to that, and the use of weighted baseballs and differential command balls to help train command, let’s review the common trap athletes and coaches fall into regarding command improvements.

“Dialing It Back”

A major reason command is trained infrequently is that many coaches and athletes, particularly at the amateur level, believe command is increased by sacrificing intent (and in turn velocity).

This is a common misstep as it pertains to human kinetics and motor control. Practically, it has negative implications during competition as well. As you can imagine, mechanical efficiency decreases, meaning proper kinematic sequencing is disrupted and velocity goes down. In other words, it’s likely tougher to command the ball, but it is also being attempted at lower velocities. In the event that the pitcher does throw strikes—well, we know how that ends.

Coaches communicate this in some form or another and most of the time verbally in bullpens, flat work, and especially competition:

“Dial it back, just throw strikes!”

“Don’t overthrow.”

“Take a little off and throw strikes.”

“Just play catch.”

There are countless examples and, as is usually the case with non-specific verbal cueing, they are largely ineffective. Because of this, athletes often feel or are told that throwing strikes cannot be achieved at maximum or near maximum effort or velocity. Failure to comply or execute on this leads to writing off the issue as mental. It certainly could be, but it is likely a lack of skill development as command is not as simple as just choosing to throw strikes.

Even if the idea of “dialing back” or “throttling down” to throw more strikes is not introduced or endorsed by a coach, amateur pitchers adopt this philosophy often on their own. This is especially the case in times of adversity.

Amateurs vs. Professionals

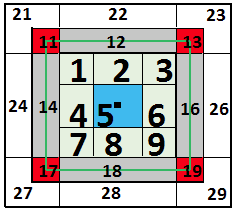

This is not something we see as a major issue with professional pitchers. Here is a chart comprised of data pulled from the Statcast:

The chart shows the average fastball velocity for all fastball types (4-seam, 2-seam, sinker, and cutter) thrown by each pitcher in the 2017 season based on location.

In Zone = A Strike

Out of Zone = A Ball

Edges = Borderline Pitch

We should see some discrepancy here if we are to assume any type of trade-off exists. We don’t. Yes, this is only a handful of professional players—a small sample. However, the data is there, and we have a previous post exploring this you can investigate.

Effective training programs improve proprioception and teach the athlete to throw with greater efficiency. This means that velocity and command will both improve rather than one cannibalizing the other. So what do motor learning, control, and human kinetics say about this?

A Closer Look

The idea that pitchers should decrease intent or effort in order to increase command is likely derived from the Speed Accuracy Trade-Off (SATO) as it pertains to motor learning and control. In short, an individual will sacrifice speed for accuracy, or vice versa. This suggests that in order to increase command (accuracy), intent or effort (speed) must be sacrificed. Speed in such instances does not directly refer to pitch velocity; it actually refers to the speed at which the movement is performed. Intent and velocity can really be interchangeable for the purposes of this discussion as we know that one is required and precedes the other. It is safe to assume in most cases when someone lowers effort or intent, velocity will drop off as well.

Academically, SATO has been researched extensively but remains poorly understood when it comes to sport (ballistic, multi-joint movements that require force production), where both accuracy and speed are required. SATO’s applications to sport and the accompanying research has revealed that there are exceptions.

More than anything, the goal and kind of task or movement is really what drives SATO’s impact. The actual effect is vastly different between throwing a baseball versus moving a mouse pad. One is a gross motor skill; the other can be categorized as a fine motor skill.

Work on the subject by the likes of R.A. Schmidt, author and co-author (newer additions) of Motor Learning and Performance, suggests that when both accuracy and speed are required within the same task, greater focus on speed is beneficial. This greater focus has a positive effect on movement, sequencing, consistency, and accuracy.

M.A. Urbin, David Stodden, Rhona Boros and David Shannon actually conducted a study called Examining ImMotus Variability in Overarm Throwing that produced some interesting insight:

The purpose of this study was to examine variability in overarm throwing velocity and spatial output error at various percentages of maximum to test the prediction of an inverted-U function as predicted by imMotus-variability theory and a speed-accuracy trade-off as predicted by Fitts’ Law.

The study went on to state the following in its discussion section:

Decreased variability in throwing velocity at higher percentages of force output demonstrated in this study suggests sacrificing speed for accuracy in ballistic skills may be detrimental for motor skill development, especially in early skill acquisition (Roberton, 1996). The lack of differences in the projectile’s spatial error over the spectrum of force output suggests that maximum projectile velocity should be promoted early in skill acquisition. In essence, if an individual exhibits less variability in force output at near-maximal levels of throwing velocity, practitioners can address preparatory limb configurations to alter spatial error of the projectile. Effecting change in the preparatory positioning of segments is arguably more accessible than manipulating the magnitude forces and torques and timing of segmental interactions that may be more variable at submaximal effort.

Plenty of other research in the field specifically looking at sport-related movements point to similar conclusions. Having athletes dial back intent and effort levels very likely leads to undesirable mechanical changes. Arm speeds decrease, but it’s very difficult for the other moving parts within the delivery to do the same. Kinematic sequencing is thrown off, which certainly will have a negative impact on command.

The answer is not dropping effort or intent. Rather than preaching this, we should be communicating to athletes to treat command as a skill and learn to command the ball at higher levels of intensities and high velocities. Training methods to improve command should be designed with this in mind.

Comment section