Exploring Causes of Decreased Hip Mobility

One of the most common goals I hear from the athletes I work with at Driveline Baseball is the desire to improve their hip mobility. Since proper range of motion in the hips is associated with improved performance and decreased risk of injury, this is a great goal to have (4, 5). In my experience, complaints of hip tightness can have an actual, measureable restriction on range of motion, or athletes can have a “normal” range of motion but still experience tightness in their hips.

Searching across the internet produces a variety of results on why hips can become restricted and the fixes for them. However, I want to share the reasons that I’ve found as to why athletes complain of decreased hip mobility. Not every athlete falls into one of these categories, and if they do, it does not mean that there are not other possible factors—listed here or not.

Hip mobility is complex, and at the end of the day, some athletes may need to go seek a healthcare or strength and conditioning professional to help them achieve their goals. That being said, let’s take a look into possible factors contributing to this problem.

Weakesses in the Hip Stabilizers

First, and probably the most easily identified factor is actual weakness in the hips and surrounding muscles. Athletes can have a good squat or deadlift and still be weak in the hips and the adjacent areas. Weakness in the glutes (maximus, medius, and minimus), hamstrings, trunk musculature, hip external rotators, adductors, and flexors can lead to muscular imbalances, creating feelings of tightness in the hips and pelvis.

An easy way to think about this is to consider someone at the gym who always works on his bench and overhead press but neglects his scapular musculature and rotator cuff. In all likelihood, this guy will have very poor shoulder mobility.

Conversely, but still applicable, this can often be the case for those who feel like their hips are tight, but when they get assessed, they actually have a high range of motion—not just in the hips but also in the majority of joints in their bodies. These athletes can demonstrate poor strength and stability in their hip joints. Without good control of a joint, the musculature around the area may start tightening as a protective means to reduce the amount of stress placed on that body part. The more range one actually has, the more strength he may actually need to maintain control and stability of his hips.

Poor Stability of the Lumbar Spine

Another reason the hips can have reduced mobility is decreased stability of the lumbar spine. I’ve discussed in a previous blog post how it is not uncommon for baseball players (and other young athletes) to develop a spondylolysis (a stress fracture, or reaction) at some point in their careers. One of the signs of this, and something that can remain lingering after other signs and symptoms clear up, is hip tightness (2).

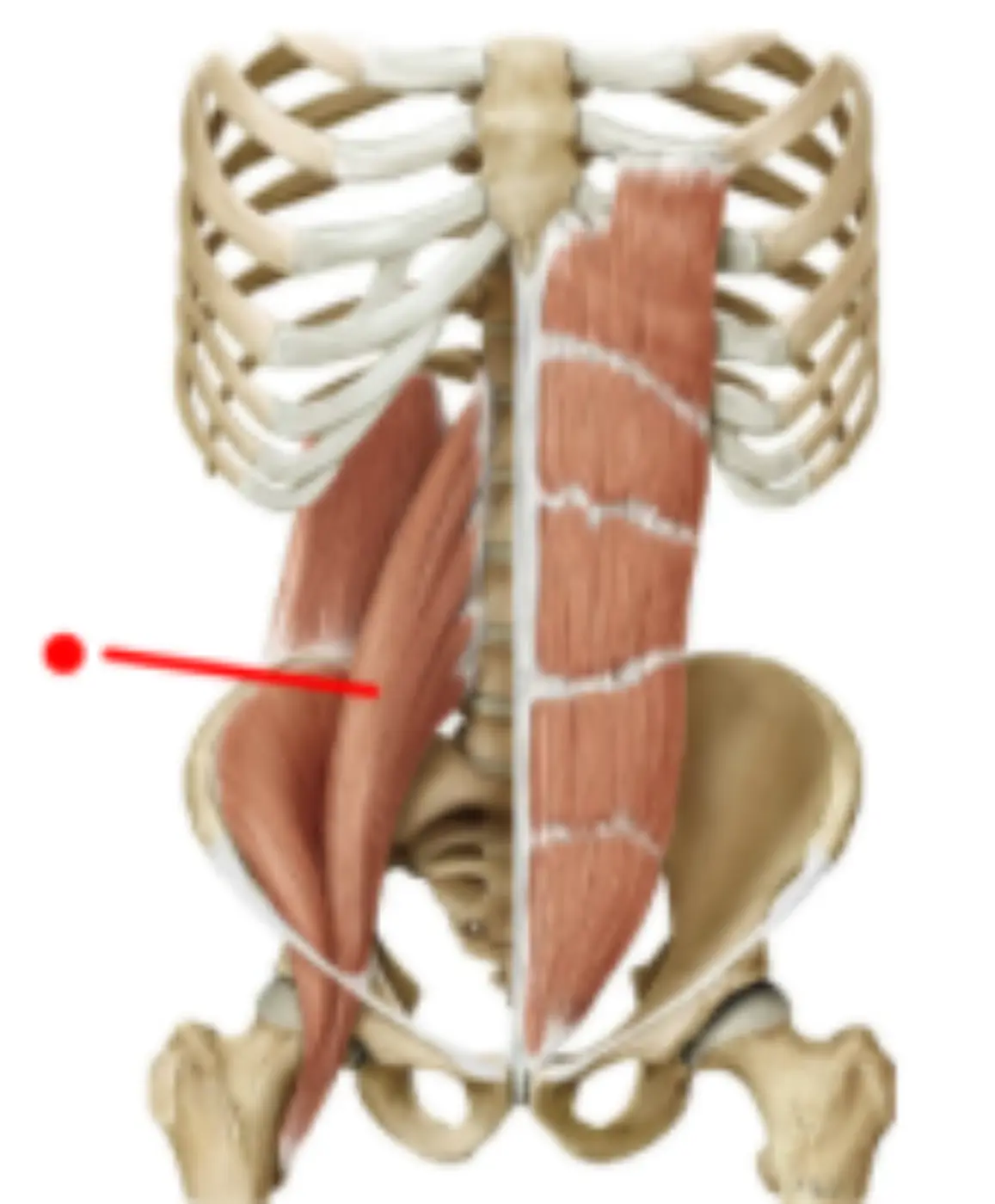

Specifically, this can happen in the psoas major, a main hip flexor, which is also part of the core musculature that helps stabilize the spine (3). When the spine is injured, the deep layers of the psoas, which attach directly to the spine, become weak and atrophied. As a result, the superficial layers can take over and become very tight (2). This can happen on one or both sides of the spine. This tightness, if pronounced enough, can affect motion in all directions of the hip. Importantly, this tightness, along with other signs and symptoms of a spondylolysis, can be present in the absence of pain. If an athlete has any worries that he may fall into this category, he should seek the opinion of a healthcare professional.

Poor Positioning of the Pelvis

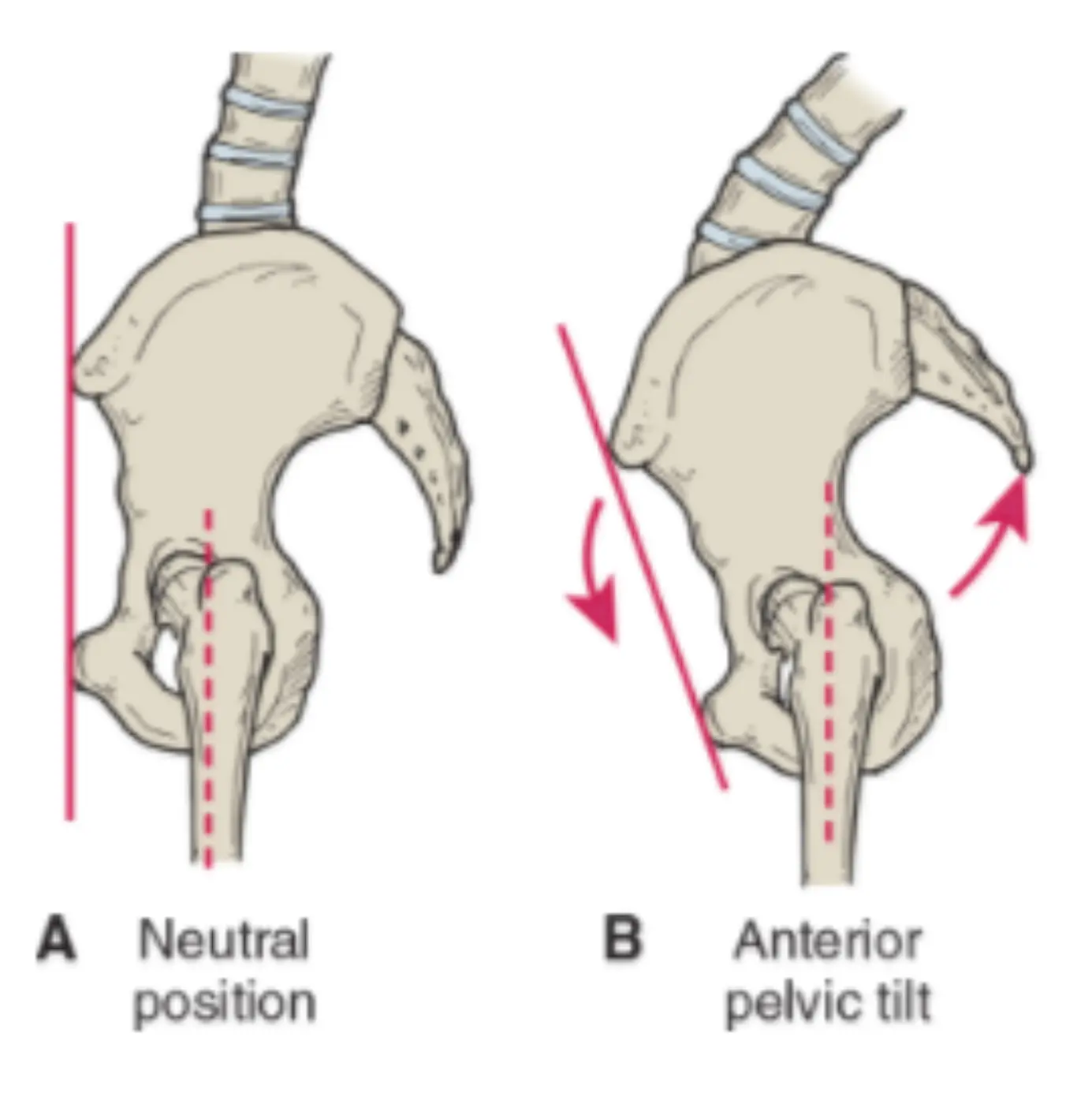

The third possible factor that can contribute to decreased hip mobility is inefficient positioning of the pelvis. Excessive pelvic tilt is a commonly discussed trait found in many athletes, as well as the general population. There are many thought processes—the Janda Lower Crossed Syndrome, and the Postural Restoration Institute Posterior Exterior Chain (PEC)—that state that tightness in the lumbar extensor muscles and hip flexors essentially outweigh the weakness of the hamstrings, obliques, glutes, diaphragm and lower abdominals and as a result, the pelvis tilts forward anteriorly (1).

Over time this can become the body’s default position. When the pelvis is rotated forward, a couple things can happen. First, the muscles that attach to the pelvis, femur, and spine can be placed into either a more lengthened or more shortened position. This can lead to those muscles not being able to stretch to their full capabilities. In addition, these muscles can also be put at a mechanical disadvantage where they are not able to contract optimally (1).

Second, the acetabulum (the “socket” of the “ball and socket” joint) can shift forward. As a result, the head of the femur (the “ball” part of the joint) will not be centered into the socket. This will lead to the neck of the femur prematurely running into the rim of the socket when the hip is moving through certain ranges (1). This can be accompanied by a feeling of a bony restriction.

As you can see, hip restrictions represent a very complex challenge that often can’t be fully addressed with standard stretching and mobility exercises. Athletes who have been dealing with this issue for a long period of time should consider working with a health or fitness professional to get a good, proper assessment to help them find the underlying causes of their plateaued progress. For many athletes, this could be an important piece for their future health and performance.

This post was written by Terry Phillips (DPT), Driveline’s in-house physical therapist. Terry specializes in manual therapy, orthopedics, sports medicine, and post-surgical rehabilitation.

- Anderson, James, MPT, PRC. “Myokinematic Restoration: An Integreated Approach to Treatment of Patterned Lumbo-Pelvic-Femoral Pathomechanics.” Kirkland, WA. 17 Oct. 2010. Lecture.

- Looper, Mark, and Ken Cole. “CORE-tical Control: Linking The Extremities H Through Neuro-Muscular Control.” Olympic Physical Therapy, Kirkland, WA. Lecture.

- O’Sullivan, P. B. “Lumbar Segmental ‘instability’: Clinical Presentation and Specific Stabilizing Exercise Management.” Manual Therapy. U.S. National Library of Medicine, Feb. 2000. Web.

- Robb, Andrew J., Glenn Fleisig, Kevin Wilk, Leonard Macrina, Becky Bolt, and Jason Pajaczkowski. “Passive Ranges of Motion of the Hips and Their Relationship with Pitching Biomechanics and Ball Velocity in Professional Baseball Pitchers.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine 38.12 (2010): 2487-493. Web.

- 5. Sauer, Eric L., PhD, ATC, FNATA, Kellie C. Huxel Bliven, PhD, ATC, Michael P. Johnson, PT, PhD, OCS, Susan Falsone, PT, MS, SCS, ATC, CSCS, COMT, and Sheri Walters, # DPT, MS, SCS, ATC, CSCS. “Hip and Glenohumeral Rotational Range of Motion in Healthy Professional Baseball Pitchers and Position Players.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2014. Sage, 8 Nov. 2013. Web.

We’ve published other articles summarizing our research, check them out here!

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

js -

WOW! Great article!!! Lack of comments spaeks to how much athletes & trainers undervalue critically important mobility @ the hips for athletes.