Are “Safe” Training Methods Causing More Injuries?

I spoke a little bit about the consequences of safety from a baseball training side in a previous blog post, but there’s another side of this paradigm, which is a little counterintuitive – it’s possible that baseball training methods geared towards “safety” and “injury prevention” are indeed actually causing more injuries.

Vern Gambetta on the HMMR Media / GAIN Podcast had a few things to say about this phenomenon. When he was first getting into professional baseball in the 1980s, light dumbbell shoulder exercises like empty can raises and lateral raises were very popular, and still are today. They are colloquially known as “Jobe” exercises, named after Dr. Frank Jobe, the legendary orthopedic surgeon. Vern said:

Just doing injury prevention exercises… it’s not working, I don’t think… The first thing I saw everyone doing were “Jobe” exercises. We were able to prevent shoulder injuries by getting rid of the “Jobe” exercises… but the focus then became the kinetic chain, the shoulder is only one link in the kinetic chain…

Vern goes on to discuss how building a holistic and transparent program that has so-called “injury prevention” built into the programs and discusses why single-joint exercises and highly-specific light load exercises are indeed not that useful.

The podcast is a great listen, so I highly recommend checking it out at the above link. We’ll reference it a few more times in this article.

Getting too Fancy: Relying on Overly Detailed Assessments

Later while Vern was working with an NBA team just a few years ago, he stated the entire roster went through a detailed evaluation about their athletic abilities:

Elaborate evaluation of each athlete… designed to find every deficiency of each athlete about what they could not do… they designed a remedial program but weren’t doing the normal strength program but were still expected to play. This team had the highest number of injuries in the NBA that year! This is ridiculous! They were never training for the game – they were doing low-demand type of work that was designed to address these perceived deficiencies tested in an isolated manner, not an integrated manner.

Inappropriate and too-early specific training to “fix” mechanical and athletic flaws in athletes when their raw output is so low is not only a waste of time, but potentially very injurious. By definition, an athlete with a low ability ceiling cannot meaningfully complete rehabilitation or highly-specific movement retraining modalities with any sort of effort or output that is effective at changing things. High-output constraint training using overload implements (wrist weights, Plyo Ball ®) create a much better bang for the athlete’s buck, developing not only mechanical efficiency but physiological improvement instead of targeting a faulty motor pattern and prescribing advanced exercises that are much better left to the elite athlete who can actually use the transfer properly.

Here’s a sample assessment of an athlete here using a few of the tools we have at our disposal.

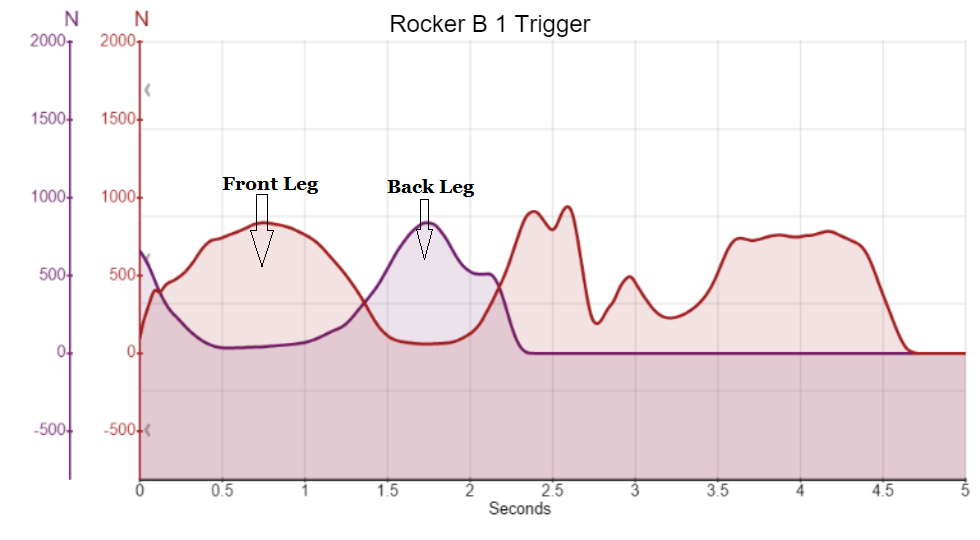

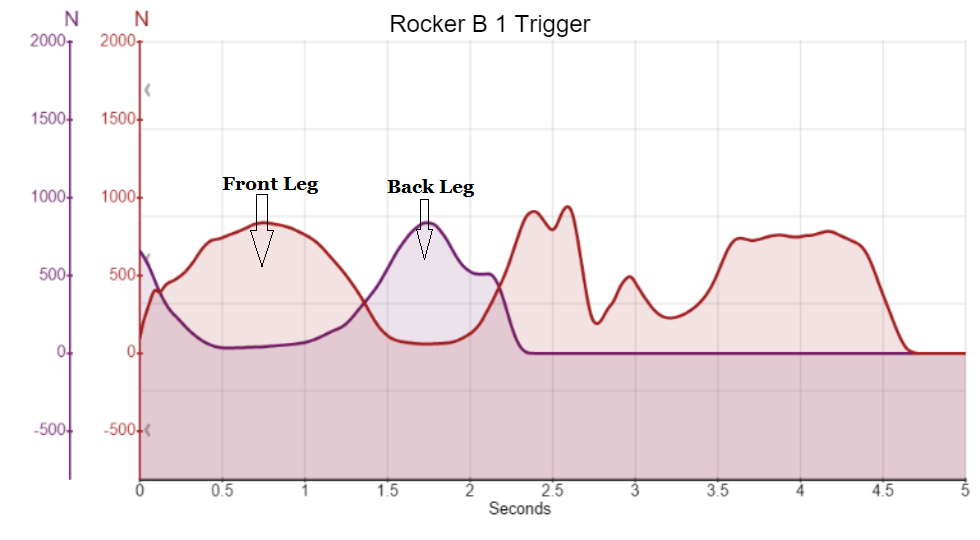

The first graph is a Force Plate analysis of a Rocker Throw (constraint drill) to test the athlete’s ability to transfer force from the back leg to the front leg, block the force, and decelerate. The second graph is a true Biomechanical Analysis of the athlete throwing a max effort fastball off the mound while being filmed using multiple synchronized high-speed cameras, which is turned into a ton of kinematic parameters (shoulder IR angular velocity, elbow extension angular velocity, pelvic speed, hip rotation, torso flexion, etc) – this one happens to be Shoulder Internal Angular Velocity.

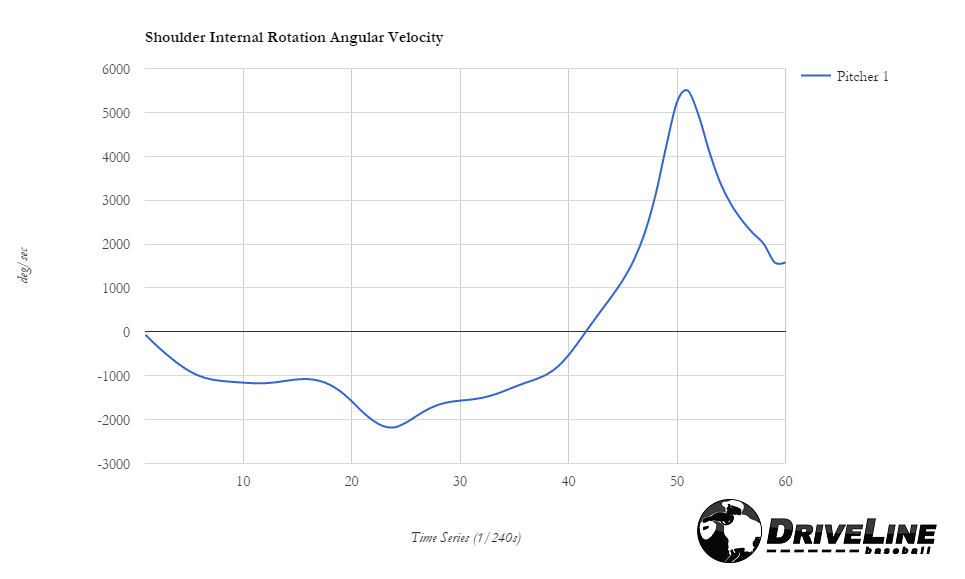

This is what shoulder internal rotation looks like, before we go too far off the rails:

Finally, two more markers we measure for this athlete:

- Max Throwing Arm Grip Strength: 97 lbs.

- Max Throwing Arm IR/ER Isometric Strength: 15.1 lb / 12.9 lb

The way we would address any flaws based on these readings is highly dependent on two MAJOR factors that are usually overlooked: Age of athlete and ability level of the athlete.

If the athlete in question had all those markers above and threw 75-78 MPH and was 15 years old, it would be highly inappropriate to design an advanced sport-specific program to shore up a bunch of deficiencies (poor lead leg blocking deceleration, faster-than-average external rotation angular velocity, poor ER/IR isometric strength balance), because your general program should be good at addressing these things! If your everyday work does not address these issues in the weight room, throwing program, and warm-up / recovery period, then your program is poorly designed. Now, if the athlete was a 23 year old professional pitcher who threw 93-96 MPH, you would trend further down the sport-specific ramp and work closely to eliminate flaws due to the high amount of energy inherent in the system despite the flaws present.

Inappropriate Program Design

Mark Rippetoe (author of Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training, amongst other great books) discusses this at length on his website and his books. Rippetoe’s argument is that single-leg and increasingly specific “rehabilitation” exercises do not transfer well to the athletic and total movement required, since coordination and strength is inherently lower when the movement is further isolated.

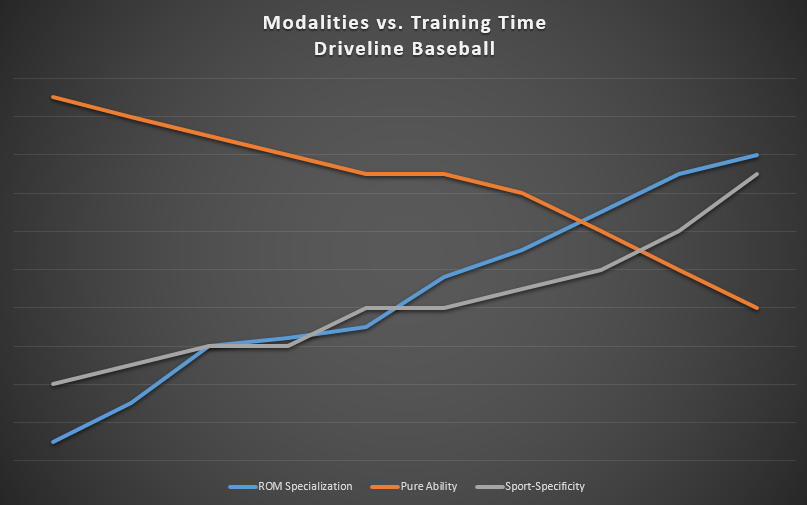

Here’s an example chart of importance (y-axis) and time (x-axis) of an athlete’s training program at Driveline Baseball as measured by three outputs:

- ROM Specialization: Decreasing the Range of Motion (ROM) of an exercise to develop shorter, quicker, more specific imposed demands

- Pure Ability: Raw output training – high-intensity throwing, lifting, training

- Sport-Specificity: Skill-based work, spin, command, blending high-output training with skill-specific work

As time goes on and the athlete builds a better engine (ability), increasingly higher demands of sport-specific work is imposed on the athlete through ROM restriction and skill-specific work. The problem is when the graph is reversed or incorrectly aligned – doing more and more isolated and single-joint “rehab” work at low demands not only has poor transfer of training characteristics, but does not adequately prepare the athlete for competition.

A good pure ability development plan raises the floor and ceiling of the athlete’s ability and challenges them above their in-competition loads, ensuring that the game’s output is consistently lower than what they experience in the training room. It’s the logic and reason behind the phrase: “Game day should be your easiest day of the week” and why Ray Lewis said: “You pay me for Monday through Saturday. Sunday you get for free.”

Intermuscular coordination, multi-joint, and multiplane exercises are the best way to build the base of any training program – including any program that aims to reduce injury risk. The problem begins and is compounded when trainers and coaches get too fancy, too soon, and with too low output of athletes. One college baseball team’s pitching coach told me that nearly 100% of their athletes got hurt who had programs designed by a well-known “sports science” place! When I reviewed the training material, it was clear these programs were way too sport-specific and far too ballistic in nature – without enough general physical preparedness or raw strength – that when it came to game time and competition, they simply did not have enough underlying coordination and strength to handle the imposed demands, despite being really good at sport-specific movements. This is a real risk when you do not adjust your programming based on the athlete’s output level.

At the end of the day, trying to reduce injury risk by “assessing” and attacking it directly can often lead to worsening problems. Do not ignore general (GPP) before specific (SPP) work, and never neglect GPP maintenance in elite athletes. It’s a plane ticket to soft tissue injuries and severely hampered recovery markers.

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

MASH Report (4/4/16) | FanGraphs Fantasy Baseball -

[…] Kyle Boddy (link) and Mike Reinold (link) both go into the mechanics and how they may cause (or prevent pitcher […]